Algorithm DetailTry ItDownload CodeContact

Algorithm DetailTry ItDownload CodeContactSINGLE TRANSFERABLE VOTE IS A REPRESENTATIVE, FAIR AND FLEXIBLE VOTING SYSTEM

This website promotes the use of a special version of the Single Transferable Vote (STV) method of counting for the next parliamentary elections. People are asking for early elections but can’t seem to agree on an electoral law.

The choice of a voting system is one that even the most advanced democracies still struggle with. The limiting factor is our reliance on manual counting methods. Allowing computer algorithms to do the counting instead, we can achieve much better results. If the solution was simple and obvious, we would have found it by now.

We will start by analysing previous or proposed systems to have a better understanding of the problems that STV solves.

MAKE YOUR VOTE COUNT!

Other Systems

THE 2009 LAW:

BLOCK VOTING

The 2009 elections used a method called block voting. Voting was divided into districts with an average of 5 seats. In block voting, you write the names of candidates for each seat while respecting quotas allocated to sects (religions). When counting, each candidate gets one point for each time his name appears on a ballot. The candidates with the most points win. It can be categorized as a majoritarian system.

As with most majoritarian systems, candidates tend to organize themselves into two rival coalitions dominated by big parties. Even though voters are allowed to create a custom list, most voters use pre-printed ones distributed by their preferred party. Small parties and independent candidates have a slim chance of winning any seats, unless they compromise their ideals and join a big coalition. The voter is left to choose between the lesser of two evils. The example below is a typical outcome of block voting.

If a coalition has a marginal amount of extra votes compared to its rival, it wins all available seats like coalition A in the example above. This fosters intense competition between the two main coalitions, which encourages vote buying and gerrymandering (drawing district borders to a coalition’s advantage). This “winner takes all” outcome leaves a big amount of voters with no representation. We say these votes are “wasted” due to loss.

Another way votes may be considered “partly wasted” is when a voter’s candidate wins by a large margin. In this case the voter thinks that his vote did not really contribute anything. Either way, waste due to loss or surplus discourages voter turnout and diminishes representation.

More about Block VotingTHE 2018 LAW:

OPEN LIST PROPORTIONAL WITH A TWIST

To fix block voting’s main shortcoming, the government decided to adopt a proportional system that is reasonably representative in its original form, then added a layer of complexity with sectarian quotas allocated to seats. In Open List Proportional, voters vote firstly for a coalition, then optionally for a candidate within this coalition. The second vote is used to create the coalition’s internal ranking. Then each coalition gets a proportional amount of seats.

The advantages now gained by proportionality were offset to some degree by the lack of flexibility. Whereas in block voting, candidates were encouraged to be part of a coalition, in Open List Proportional they were forced to be. This can lead parties and independent candidates to form surprising alliances. Being restricted to a single coalition presents two important drawbacks for the voter. First, they are indirectly supporting other candidates regardless of whether they support them or not. Second, they are no longer allowed to support candidates outside of the selected coalition.

Moreover, there is a problem inherent to all proportional systems based on lists, no matter how the threshold is calculated. If a list doesn't match the threshold exactly, it will either waste the votes it has above the last threshold level, or win an extra seat with fewer votes then what the next threshold requires.

In the chart above we see Coalition A and B winning two seats each, Coalitions C winning one seat each, and Coalition D not winning any seats. The blue parts represent real votes that counted. The green-bordered parts represent votes required to reach the next threshold. The red parts represent votes that were wasted. The total waste in this example is 800 / 5,000 = 16 %. One can also observe that a coalition's surplus votes were obtained at the expense of another coalition's waste. Naturally, the more seats a district has, the lesser this effect.

More about Open List Propotional VotingPROPOSED LAW:

SINGLE MEMBER PER DISTRICT

By reducing district size to fit the election of one candidate, we benefit in several ways. Since it’s every candidate for himself, we neutralized the negative effects of parties and coalitions with their strategic alliances. The reduced size of the district means the candidates are closer to their voters. This makes them more accountable and responsive to the voters’ wishes.

There are several methods of voting and counting that differ in the way they elect a winner if a clear majority was not reached in the first round. The simplest way would be to do a second round with just the top two candidates. A better method is for the voter to write the names of the candidates he would vote for in order of preference. This is actually a perfect representation of the voter’s wish. It shows all candidates the voter approves of, and their preference. No matter the counting method and the number of rounds needed to come up with a result, at least the voters’ input is represented correctly.

The downsides of this system is the lack of proportionality. Which means it is still vulnerable to gerrymandering and vote buying. We will still most probably see a good portion of the voters having no representation. Also, It is impossible to set quotas per sect (or gender).

More about Single Member per DistrictWhat is STV?

INTRODUCING SINGLE TRANSFERABLE VOTE

STV combines all the advantages of the previously mentioned systems.

- Proportionality

- No coalitions and their negative effects

- Flexibility of voting for any candidate

- Preferential voting to accurately represent voters’ wish

- Voters no longer need to vote for the lesser of two evils

- Reduction of the effects of vote-buying and Gerrymandering

- Optional support for sectarian or gender quotas

- Very low wastage of votes whether from loss or surplus

- Allow moderate candidates to come through

Its only drawback is its difficulty in understanding the counting procedure. Check out this link: www.electoral-reform.org.uk for a quick comparison to other systems.

Below are three videos of varying length that do a great job of explaining the basics. We will then introduce the extra features that our special version has that makes it more suited to Lebanon’s requirements.

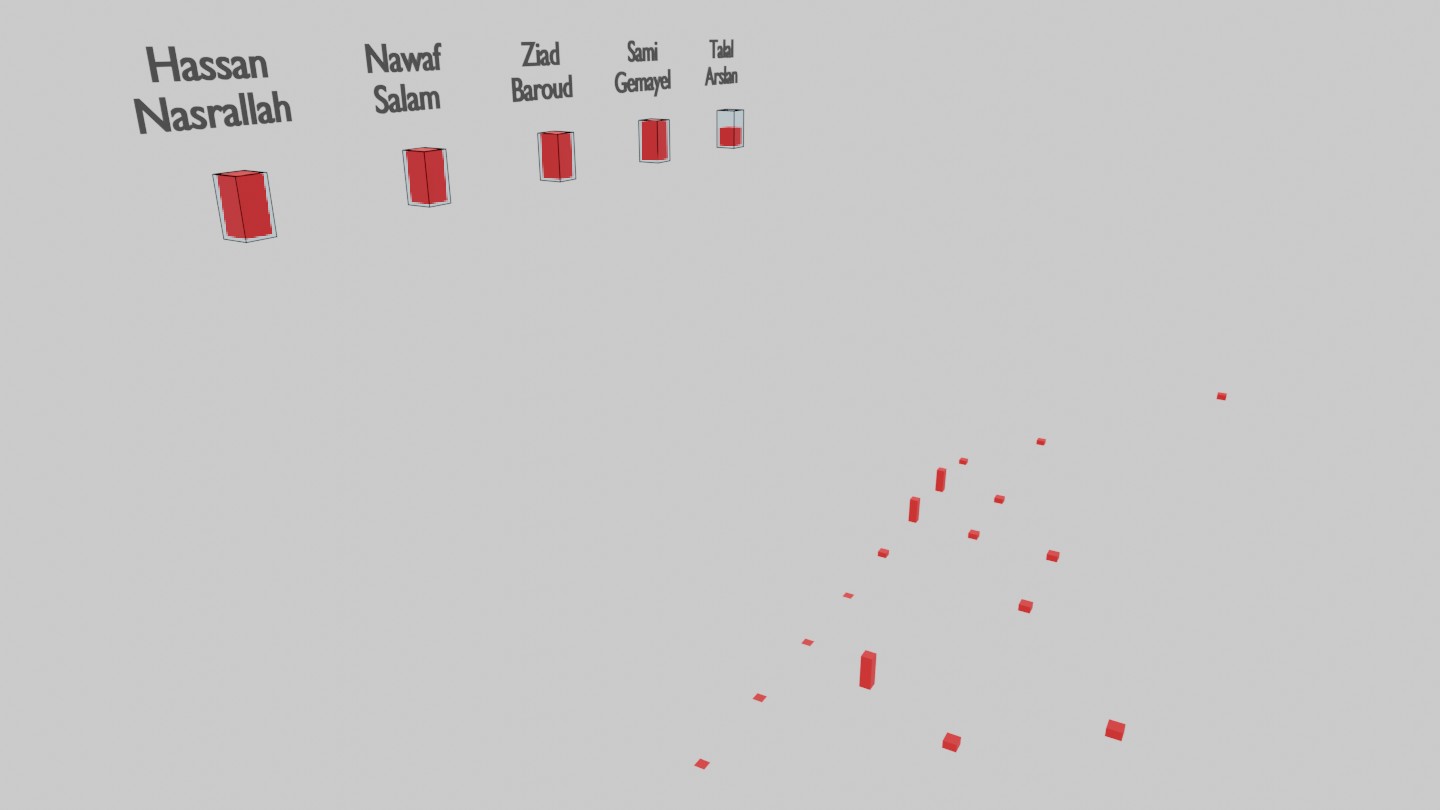

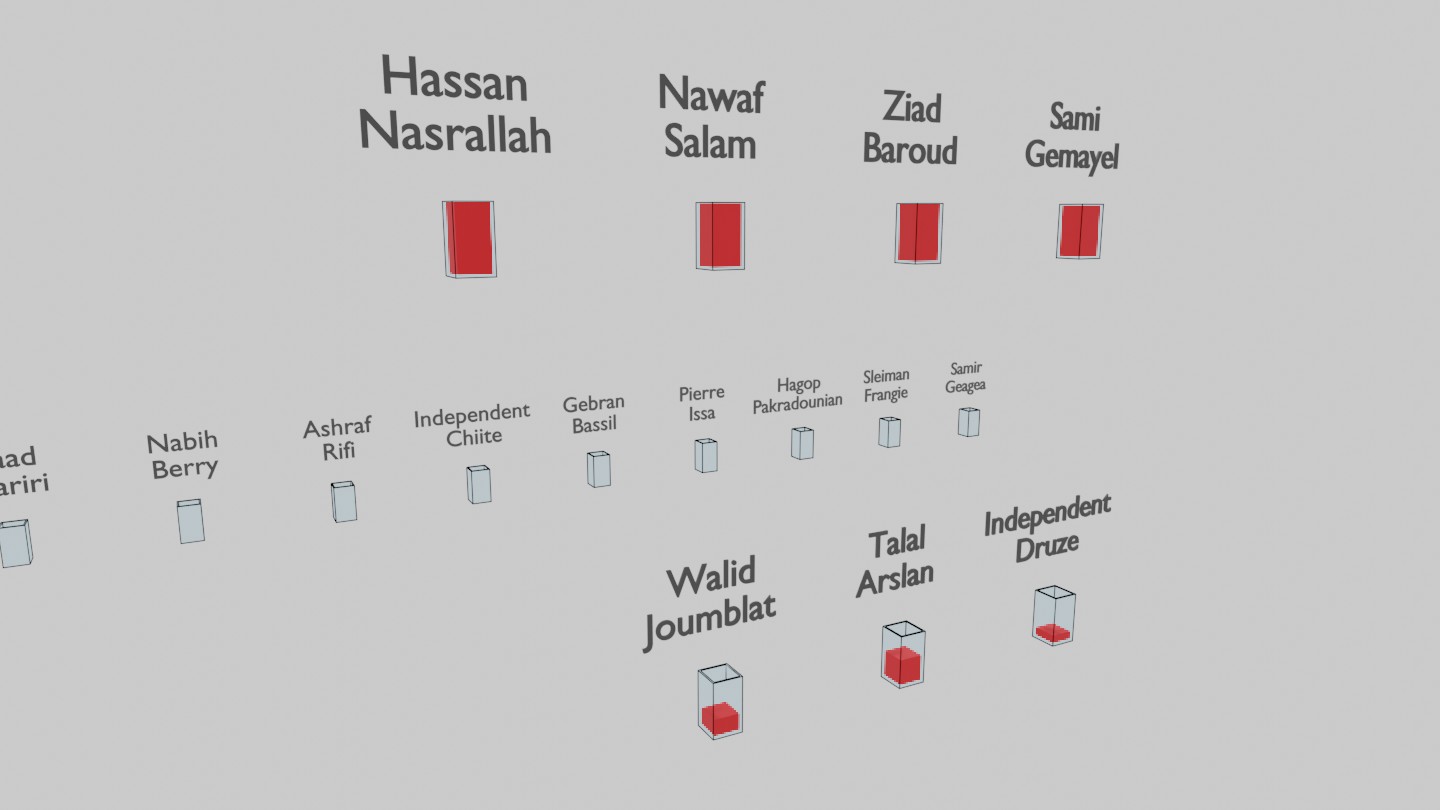

Now that we have a grasp of how STV works, let’s explore our version by running through a makeshift election for five leaders with two seats reserved for christians, two for muslims and one for a druze. First, let’s get familiar with the setup and visual conventions.

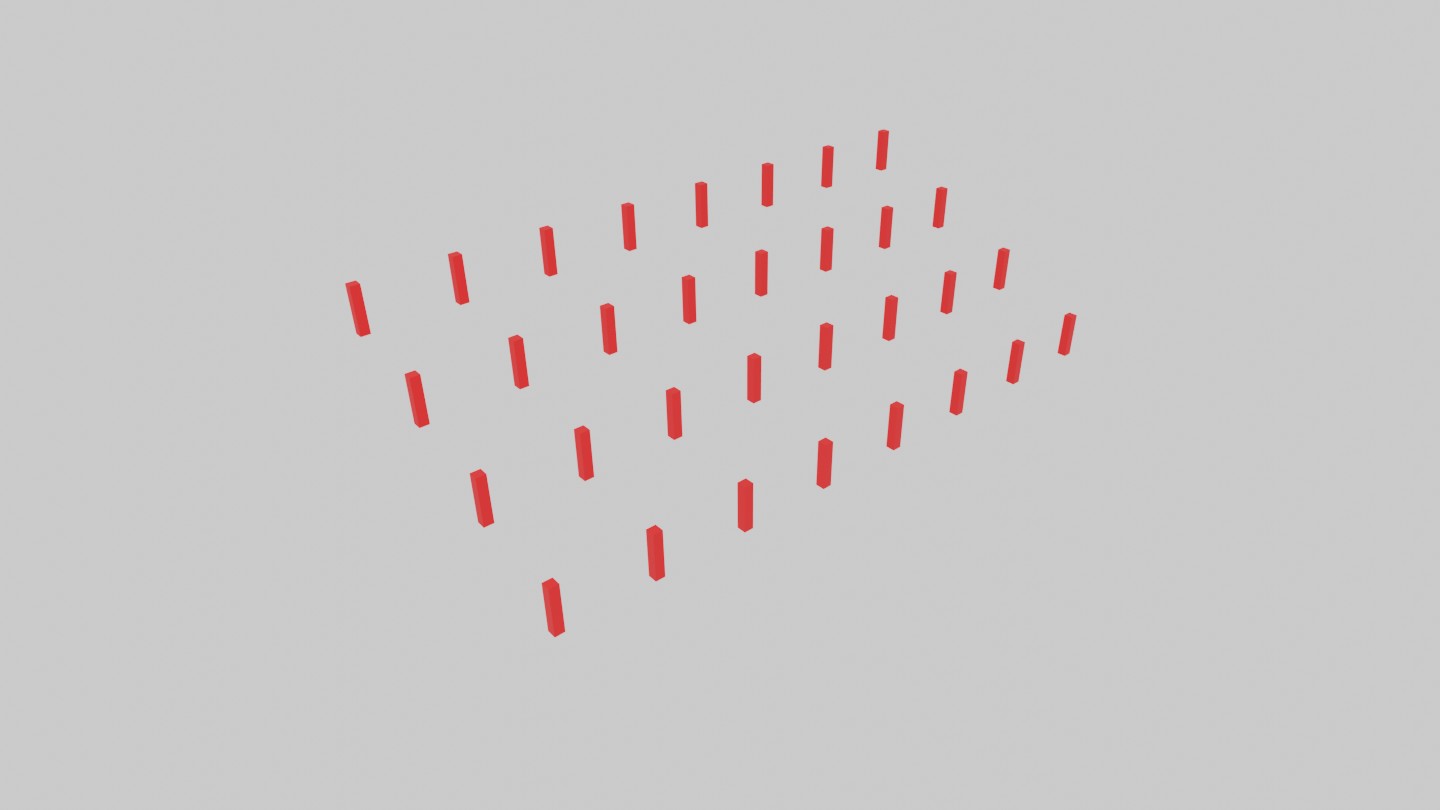

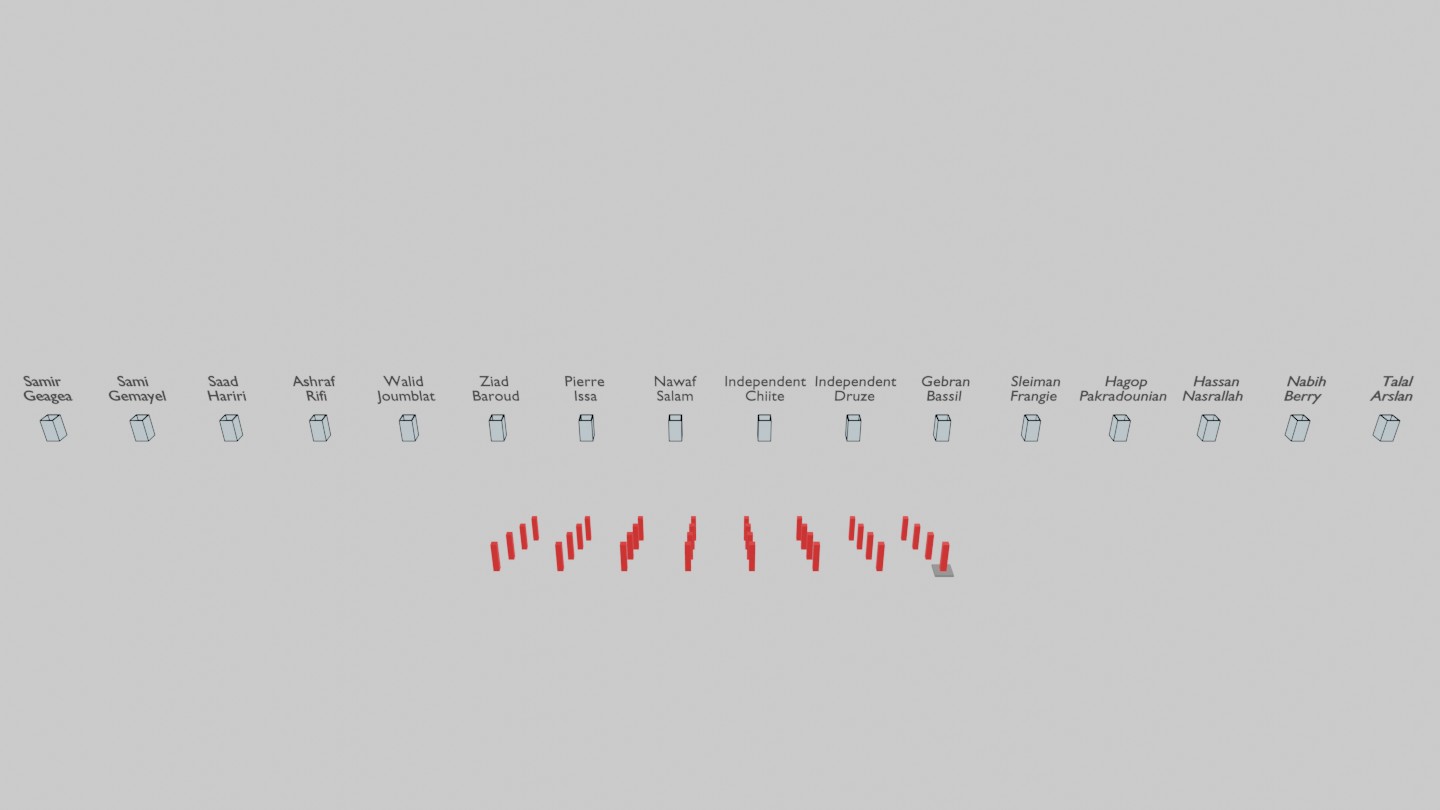

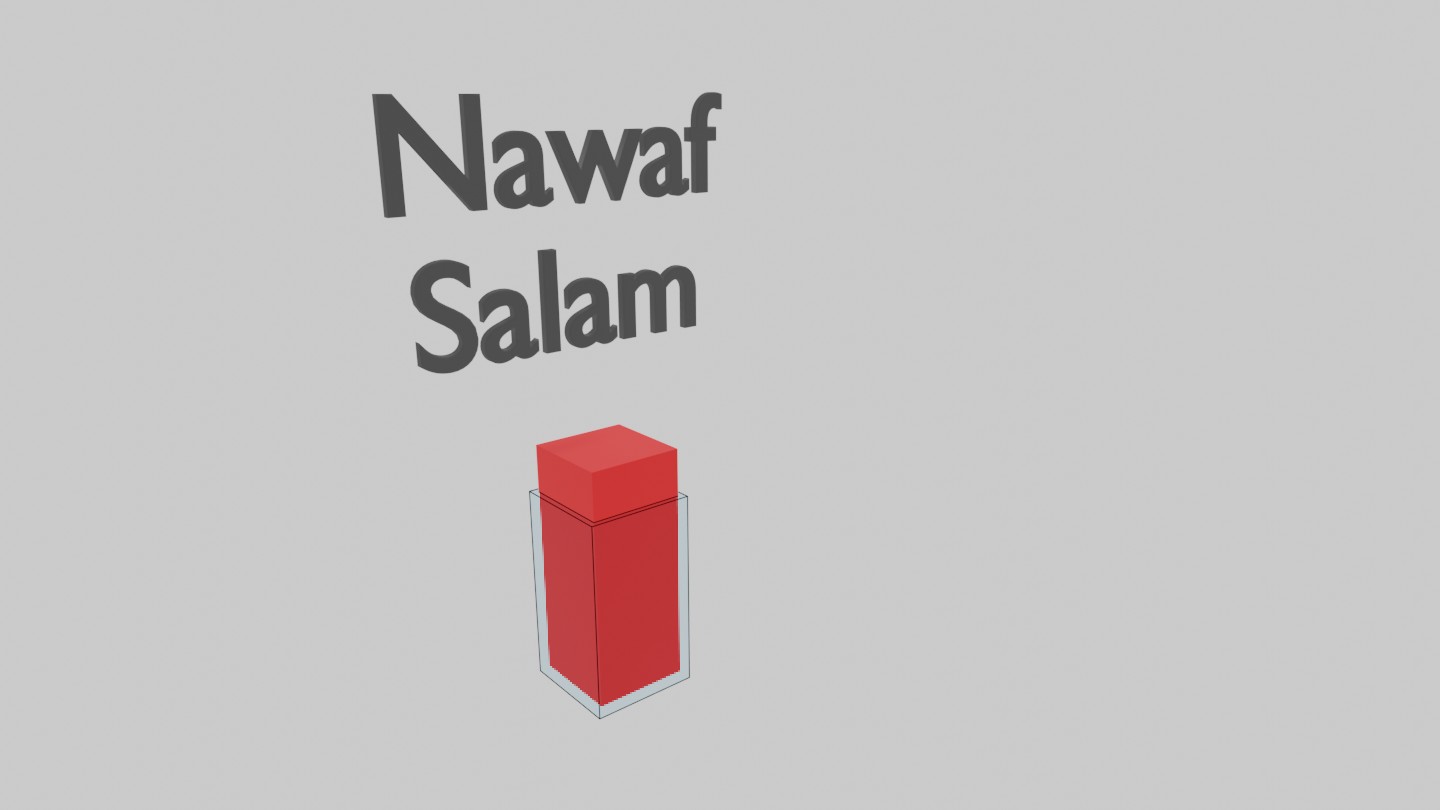

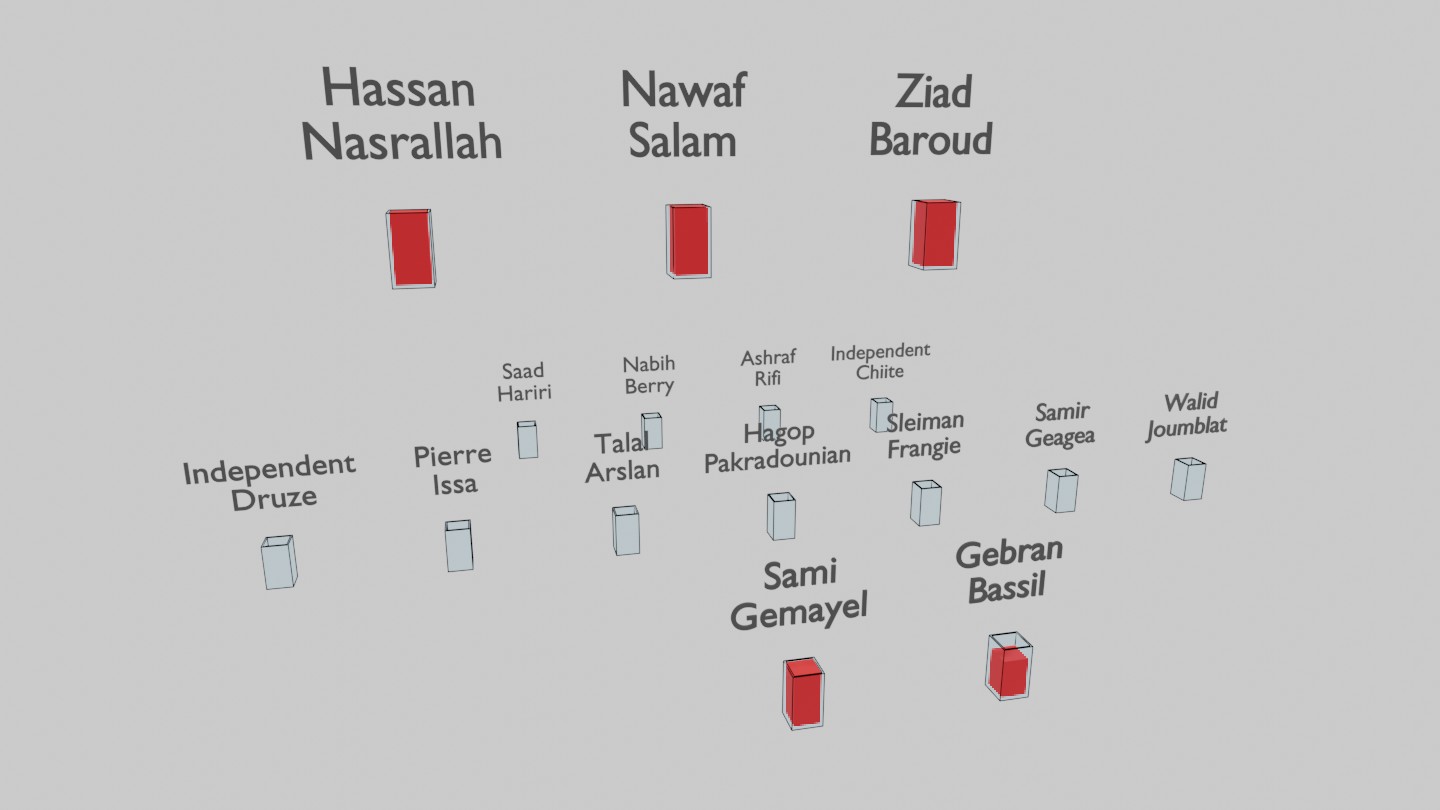

Facing our voters are our 18 candidates.

Disclaimer!The choice of candidates, the voter’s preferences and the final result were tuned to produce an election that will showcase all the features of STV, while keeping some familiarity with the current political climate.

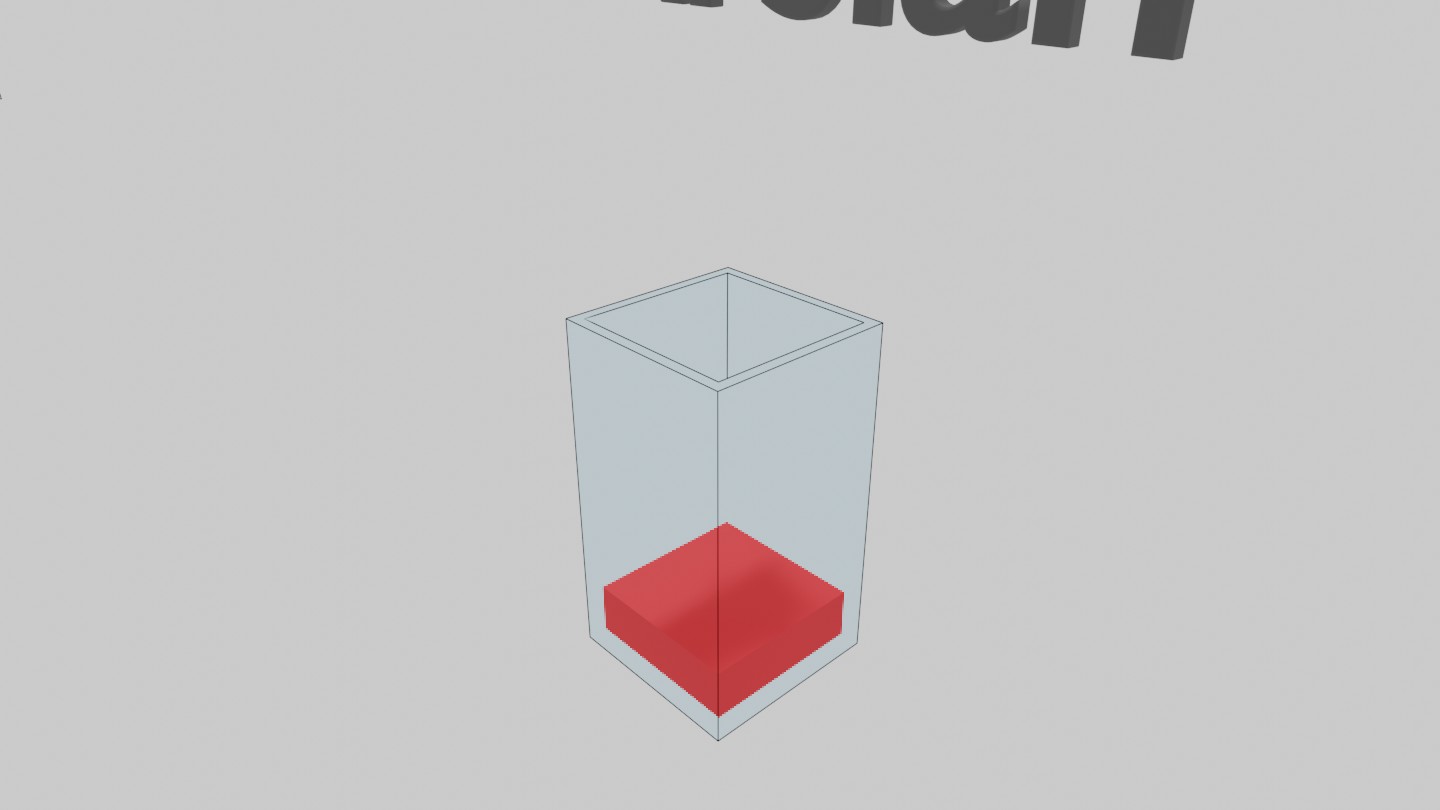

When a bucket overflows (surplus votes), it gets rid of the surplus not by returning the last votes it received above the quota. Instead, it returns a small fraction of all the votes it contains.

For example, if the quota is 6, and the candidate received 8 votes from 8 voters, it doesn't return 2 full votes to the last 2 voters, instead it returns 0.25 to all 8 voters.

GROUP QUOTAS

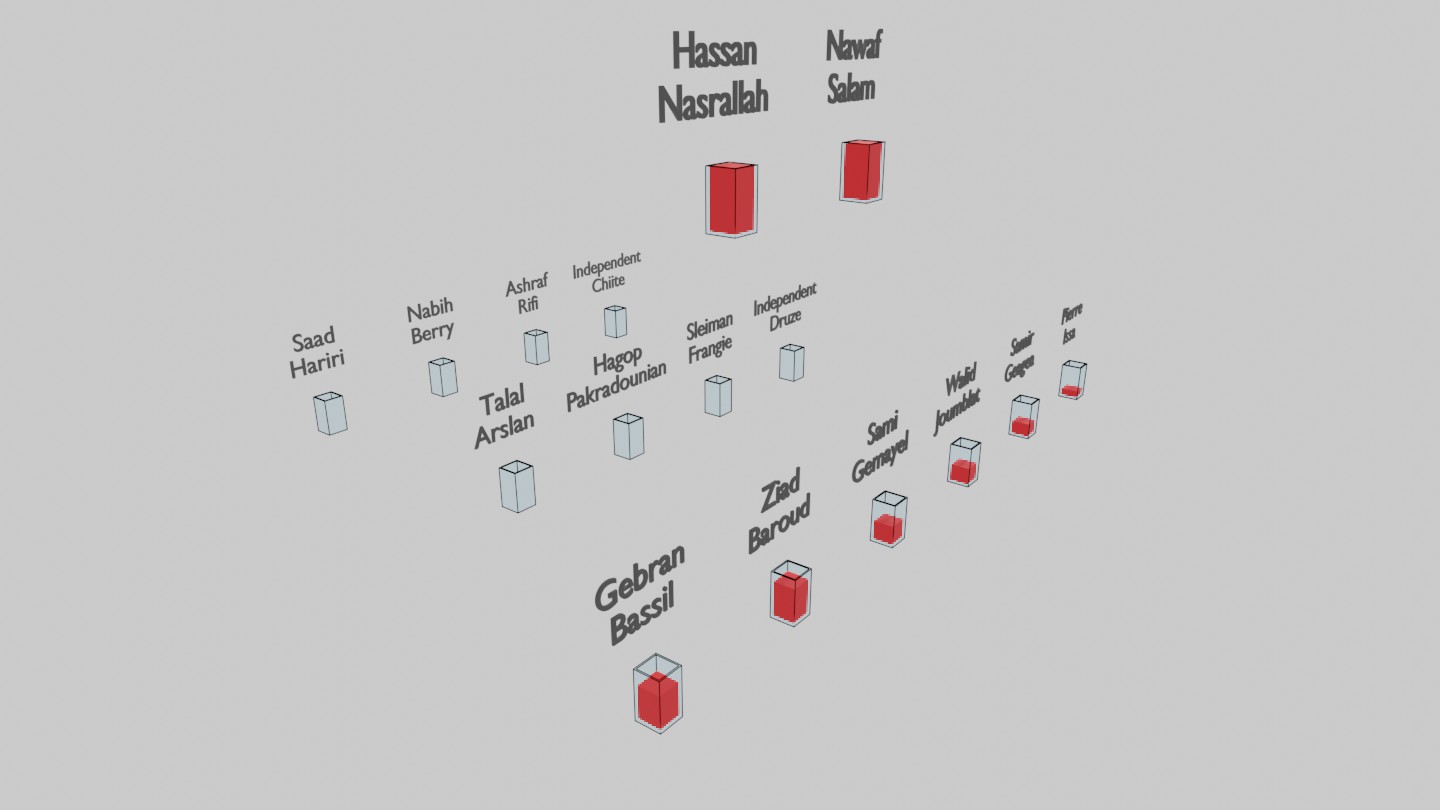

There’s a high chance that the establishment as well as some portion of the population at large, are not ready to abandon sectarian quotas. STV can be modified to be able to accommodate that. We added the concept of “Group”. Every candidate belongs to a group and every group has a dedicated number of seats. Let’s assume there are five seats in total. Two for christians, two for muslims and one for druze. During the counting, once a group’s seats are filled, we exclude from the count all other candidates belonging to this group. For example, if we fill both muslim seats, all other muslim candidates are now excluded.

The front lower row is for the active candidates. The top row is for the winners. The middle row is for candidates who lost because they had the least votes in the round. The back row is for candidates that have been excluded.

A very peculiar scenario can arise when applying group quotas. Building on the last example. Let’s assume now that the two muslim seats have been filled, and the second christian winner has just been declared filling both seats. We now exclude all other christian candidates. It also happens that there is no druze candidate left because they’d already lost in previous rounds.

Sami Gemayel is about to win, thereby excluding all the rest of the christians. There is no one left in the active candidates to potentially win the druze seat.

The solution to this issue leads us to our second feature.

REACTIVATION

The previous case forces us to “Reactivate” a druze candidate that has already lost, to fill this last druze seat. We can take this concept further and decide to reactivate all lost candidates (middle row) after every win. With this feature, there is even less wastage as consensus candidates that might lose in the early rounds can make a comeback in the later rounds. Since a computer is doing these extra calculations there is absolutely no reason not to do it.

There are a lot of other interesting details about the algorithm that will not be mentioned in this page. Visit the algorithm detail page to learn more. Below is a video of the sample election we’ve been using above. In the bottom right we can observe the progression of one of the voter’s ballot.

Implementing STV

How will we use this version of STV in real life? The core of the program is 300 lines of code written in Python (an open source programming language). It can be plugged in to a website such as in the try it page or run directly on any computer using the the command line. You can examine and audit the code directly by going to the download section.

The program needs three simple inputs.

Groups to setup the number of seats available per group.

Candidates is the list of candidates and the group to which they belong.

And Votes is the list of votes, where each line is just an arbitrary voter ID followed by a list of candidate codes.

Assuming we are using the basic command line interface the three inputs would be represented as below.

At its most basic, what is required to apply STV is simply taking each paper ballot and writing it as a new line in the Votes text file. We would then run the program and get the result in seconds with the option of viewing each step of the algorithm in the counting process.

If there’s any suspicion of tampering or cheating with the counting phase, we would only need to audit the paper ballots against the input text file.

As far as parliamentary elections are concerned, drawing the voting districts and allocating seats per sect is always a sensitive issue that takes a lot of time and effort to settle. We can keep the 2018 districts and seats as is and only change the ballot to STV.

Promoting STV

Hopefully we have convinced you that STV is the ideal system for the next parliamentary elections. You are encouraged to visit the try it page, download the program, examine the algorithm, and share your opinions. Feel free to use this version of STV in your own organisations as an experiment.